Volcanoes and Pine Barrels

In March 2019 I had the good fortune to be invited to visit the Canary Islands by Gabriel Santós of La Laguna University in Tenerife. At the university I met young winemakers, and tasted and discussed their red, white and rosé wines.

With young winemakers of the Canaries

I also visited a few vineyards, where, because of the region’s isolation from the mainland, phylloxera never arrived in the Canary Islands, meaning that vines can be hundreds of years old, often trained using traditional methods.

We discussed the local market for Canary wines – largely in small restaurants frequented by locals or the more adventurous tourists and the high-end gastronomic restaurants. The majority of the market, largely for the tourist sector, apparently relies on cheaper, imported wines. Many vineyards are small, and selling locally is more profitable than exporting, resulting in these wines remaining relatively unknown.

This has not always been the case. The Canary islands, located off the north western shore of Africa, have been a useful port for sailors for centuries, with a multi-cultural heritage, including Berbers from north Africa, Portugal, Spain and Britain. I particularly liked their expression for someone who has a mixed background ‘mille leche’.

Sailors and merchants who came to the islands loved the local sweet wines and a flourishing Anglo-Spanish trade with the Canaries developed. This was, however, brought to an abrupt end in 1666 when islanders rebelled against the dominance of the London-based Canary Island Company, which had a monopoly on exports. When producers expressed their discontent by smashing barrels so that Malmsey flowed in the streets, Britain retaliated by banning the wine and moved to the Portuguese wines of Madeira.

This has not always been the case. The Canary islands, located off the north western shore of Africa, have been a useful port for sailors for centuries, with a multi-cultural heritage, including Berbers from north Africa, Portugal, Spain and Britain. I particularly liked their expression for someone who has a mixed background ‘mille leche’.

Sailors and merchants who came to the islands loved the local sweet wines and a flourishing Anglo-Spanish trade with the Canaries developed. This was, however, brought to an abrupt end in 1666 when islanders rebelled against the dominance of the London-based Canary Island Company, which had a monopoly on exports. When producers expressed their discontent by smashing barrels so that Malmsey flowed in the streets, Britain retaliated by banning the wine and moved to the Portuguese wines of Madeira.

The Canary islands, with La Palma to the north west

Sweet wines are still produced, but this is not the only historic wine of the islands.

On the north west coast of the island of La Palma, in the sub-zone Norte, a rare wine is produced called vino de tea. I had come across this wine when José Luis Murcia Garcia, a fellow judge at the International Rosé Championship, suggested that it could be included in my rosé book and sent me some wine.

Following my time in Tenerife I went on to visit La Palma, a short half hour flight to the west. Picking up our jeep from the airport in Santa Cruz, Gabriel, my translator Mark and I, crossed over the northern central mountains to visit winemakers in the north west of the island.

La Palma.

La Palma

The volcano, Cumbre Vieja, in the south of the island, is still active; the last eruptions being in 1949 and 1971. During the past year (2018-9) there have been numerous recordings of tremors on the island and under the sea. Recent eruptions on La Palma have not been enormous, with fresh volcanic soils in the south, being planted with Malvasia vines. Unlike the other islands, La Palma, this most westerly of the islands, has waterways, which fill with water when it rains, running through it, allowing it to have a green countryside, particularly toward the northern part of the island.

Crossing the volcanic mountains of northern La Palma

La Palma receives almost all of its water supply due to the mar de nubes (sea of clouds), stratocumulus cloud at 1,200m -1,600m altitude, carried on the prevailing wind which blows from the north-east trade winds. The peaks, the highest being 2,426m, rise above the clouds. The vineyards at high altitudes experience large diurnal temperature variations resulting in long slow maturation. The Norte region, with old volcanic soils, also has a high percentage of clay soils.

High altitude vineyards, amongst the pine trees, with cooling, damp maritime winds

View from the vineyards 1000m up looking out over the Atlantic

Vino de Tea

Only a few producers make vino de tea, from vineyards perched on terraces of volcanic soil, largely from the Negramoll variety. Also known as Tinta Negra, this grape is better known as being the workhorse grape of Madeira, despite the fact that there are far more plantings in the Canary Islands. It tends to produce wines with round tannins and fresh acidity. Other red varieties, which can be included are Muñeco or Almuñeco. White varieties such as Listán Blanco and Albillo, which tend to ripen earlier, contribute sugar and richness. Aromatic white varieties are not used because the flavours would fight with the character of the wood.

The wines, which may be white, red or rosé, but are normally red wine, are matured in tea (Te-A) pine casks for up to six months, giving them a resinous flavour. Tea is the local name for the Canary Island pine (Pinus canariensis), and the barrels are made from the red heart of the pine. which colours all the wine red.

Tea tree trunk showing the red hear of the tree

Table made from tea showing the red colour

Eufrosina Pérez Rodríguez of El Nispero (with Mark translating)

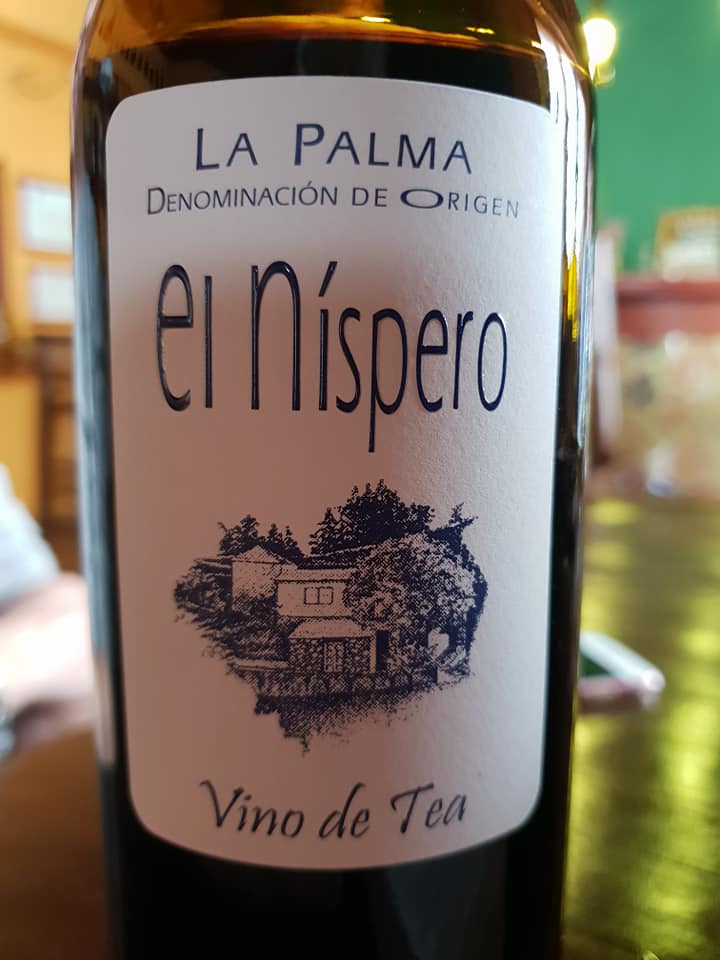

El Nispero Vino de Tea 2017. A blend of Negromoll and many other varieties. grown in vineyards around 1,200m above the clouds, with a high clay content. The wine is fermentation in tank and then the wine is passed, in batches, through a pipa de tea for 15-30 days before returning to tank and blending. Only 1,200-1,400 litres a year are made. Aromas of smoke and spice, reminding me of rich spicy sausage are followed by flavours of herbs, pine and garrigue, balanced by fresh, ripe, berry fruit.

El Níspero vino de tea

Taedium 2017 Bodegas Noroeste de la Palma, made principally with Negramoll, with some Muñeco and Listán Prieto. The wine is aged in old, 900 litre barrels. The wine had pronounced resinous, earthy notes with hints of Christmas spice. On the palate, austere, mineral, dry red fruit with fresh acidity, with a tannic edge and pine and earthy flavours. Drunk with food, the wine takes on black chocolate and menthol-pine flavours backed by very gentle, supple, dry tannins.

Vincente with his Taedium

Vinarda 2018, barrel sample. Resinous character more evident and dominant, the wine needing time to mature and the flavours to integrate. Looking forward to trying this again when out of the barrel.

David of Vinarta with his pipa de tea Admittedly, this piney taste may not be to everyone’s taste, but I loved these wines with their unique character and historic tradition.