Three Serious Bordeaux Rosés

Having to assert that there is serious wine in Bordeaux is a strange way to start this post, but mixed feelings over pink Bordeaux was certainly evident when I was researching my book on rosé. Serious rosé in Bordeaux is still a minority product which is showing considerable promise. Christer Byklum, the Norwegian Bordeaux specialist commented that in all of his visits to Bordeaux he is very rarely shown any rosé wine, ‘almost as if the producers themselves are a bit ashamed of them.’ He is more likely to taste Bordeaux rosé in a restaurant than in a cellar. He also pointed out that readers of his wine reviews are unlikely to be interested in rosé wine.

The emergence of lighter rosé

Traditionally, The red wines of Bordeaux were a light red to dark pink clairet. With the emergence of big, more structured red wines, these light clairet were often dismissed as being little more than a red wine by-product (even though that is not necessarily true). Rosé in Bordeaux was considered uneconomical, with red wine commanding higher prices and more successful sales. Clairet was made in weaker vintages, when juice might be bled off reds to make a 'weak red' or darker pink or from fruit from vines too young to make good reds. Clairet as good as disappeared until Professor Peynaud recreated the style for le Cave de Quinsac in 1950.

Rosés of the south west started to emerge as fresh, juicy, summer wines in the late 1980s. In the early 1990s, Château de Sours produced a fresh vibrant rosé which achieved near cult status. In the early 2000s, a surge in replanting vineyards boosted rosé production, but as the vines have aged, they have been increasingly used for reds.

Many of these ‘early’ rosés were slightly darker and fruitier than their contemporary Provencal rosés. In 2006, 2007 and 2008, Richard Bampfield MW hosted what turned out to be influential tastings of top Provence rosés and Bordeaux rosés to press and producers. In keeping with the fashionable trend over the past twenty years, the lighter, paler wines received great approbation, and a number of producers started to reconsider their rosé style. Around this time, an increasing number of Bordeaux producers moved towards paler, fresher rosé styles, making a more international style.

Lighter, simple, fresh and often fruity rosés, less reliant on the vagaries of vintage, are seen as way to sell wine from Bordeaux to a younger market. Promoting these more modern rosés was perceived as a means of attracting a new, younger audience to the wines of Bordeaux. In 2010 the Bordeaux Wine Board (CIVB) reviewed its marketing strategy and the role of Bordeaux in the international market and started to actively encourage Bordeaux rosé.

Bordeaux specialist Jane Anson, believes the production of rosé is growing in Bordeaux, but that there is a struggle to define a Bordeaux style and lack of a consistent marketing story ‘There are dozens of shades and styles, saignée or direct press…. And a growing recognition of what the market wants – a lighter, cleaner, fresher style, not saignée.’ Rebecca Gibb MW, who has also written on Bordeaux, commented that she is 'rarely offered a Bordeaux rosé when in Bordeaux and it's often a brightly coloured, fully flavoured offering that makes up an almost negligible part of the rosé shelf in the UK.' She went on to say 'I’ve sold Chateau Meaume and Chateau de Sours pink in my time and they are loved but only at the right price – which is often low. It remains a sideshow in the Bordeaux carnival of fine wine.'

Clairet, Rosé and Colour

The clairet market deserves a post on its own, but for now, statistics show that pale rosé production has grown to five times that of clairet. In 2011 624 ha were given to clairet, compared to 3,422 for rosé. From 2011 to 2014 Bordeaux rosé sales grew 36%. Despite these figures, production remains small, with clairet and rosé together making up merely 4% of the region’s production in 2016.

It is not only the paleness of colour that is important. For Gavin Quinney of Château Bauduc, the shade of pink itself is a strong indicator. Fresh Bordeaux rosés have a blue tinge, with no hints of orange-salmon. This is a character unique to Bordeaux rosés and comes from the terroir, its varieties and their acidity. However, as can be seen in the three rosés below, all of which have spent some time in oak, the colour has faded to salmon pink. The most obvious difference between clairet and rosé, is the depth of colour, with clairet being significantly darker, verging on pale red.

It is not only the paleness of colour that is important. For Gavin Quinney of Château Bauduc, the shade of pink itself is a strong indicator. Fresh Bordeaux rosés have a blue tinge, with no hints of orange-salmon. This is a character unique to Bordeaux rosés and comes from the terroir, its varieties and their acidity. However, as can be seen in the three rosés below, all of which have spent some time in oak, the colour has faded to salmon pink. The most obvious difference between clairet and rosé, is the depth of colour, with clairet being significantly darker, verging on pale red.

Climate, Viticulture and Vinification

The Bordeaux region has a fresh climate and a cool oceanic influence. Its interesting terroirs allow for fresh and delicate pinks from blends of Bordeaux’s traditional red varieties; Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc. In Bordeaux, some producers assess red vine plots from year to year, to decide which should make rosé wine, which red, although some estates use the same parcels every year. Generally, the cooler, fresher parcels are favoured for rosé. Although some say that the grapes used for rosé thrive in deep clay, where the plant is not stressed and the soil produces the best aromas, of the following three wines, two are in deep gravel and one with high limestone content. After flowering, vines showing rosé potential are not de-leafed, as the aim is for big, juicy berries, not the fully ripe, concentrated fruit for red wines. Often, not until the fruit starts to ripen is the final decision made over which parcel will go to the rosé vat. The rosé harvest can be between 10 to 20 days before that for red wine, with that for clairet somewhere between rosé and red. Rosés made from juice bled off that destined for red wine can lack the freshness of earlier harvest dates. Merlot, which makes up two-thirds of the region’s plantings, can easily come in a whole degree of alcohol higher than the Cabernets, and if harvested too ripe can unbalance the rosé and make it too alcoholic. Merlot is therefore typically harvested at least 10 days before phenolic maturity but ripe enough not to have the vegetal notes of unripe fruit. Research has suggested that Merlot is best macerated at a lower temperature, around 15ºC, to slow down extraction of colour and optimal fruit character. Higher temperatures give a heavier wine with less balanced freshness, unsuitable for a rosé. Twenty-four hours is generally the maximum time for maceration. The longer the maceration, especially with higher percentages of Merlot, the more fruit driven the flavours. Some recommend a very brief maceration before pressing. There is debate as to whether a brief maceration before pressing contributes colour and fruit.

The Wines

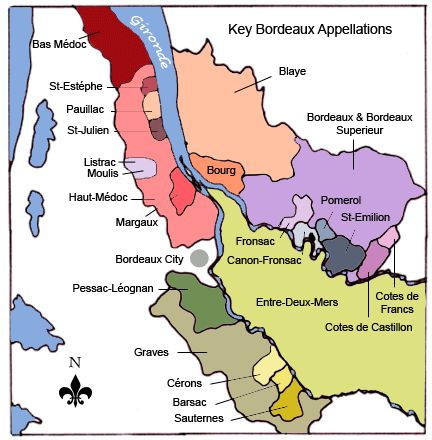

Map of the Bordeaux wine regions (https://feinwein.wordpress.com)

Château Léoville-Barton

Some grand cru classé châteaux make rosés under the appellation of Bordeaux Rosé or vin de France. Rarer than standard rosé wines and more expensive, they are popular in Asia, notably Japan. The signature rosés made by the grand cru classés are only made in vintages when the red wines need concentrating. Often vinified in stainless steel, they then go into barrel with battonage.

Château Léoville-Barton, a cru classé estate in Saint Julien, close to the Gironde estuary, produces powerful and fresh red wines dominated by Cabernet Sauvignon on the deep gravely soils. Rosé wine is not made every year, but in 2016 it was felt necessary to bleed off some juice from the red wine. The rosé was fermented at a low temperature in oak. The vintage’s high acidity has allowed for the rosé to retain sufficient acidity, despite the later harvest date. Initio is bottled as a vin de France to avoid confusion with its main wine production.

Initio 2016 Château Léoville Barton 100% Cabernet Sauvignon. An orange pink, copper colour. Sweet black cherry and blackcurrant aromas with leafy herbal notes. The richness of the fruit, with savoury undertones, gives firm weight and structure with vibrant fresh acidity, makes this a serious food-friendly wine, although I found it to be a little on the solid, chunky end of the spectrum. Definitely a rosé robust enough to serve with food and not to be wasted as a simple aperitif wine. Limited production.

Initio 2016, vin de France from Chateau Léoville Barton

Château Mangot

When Karl and Yann Todeschini joined their parents in the running of Château Mangot, a St Emilion Grand Cru, in 2008, they brought a wealth of international experience and marketing energy. In 2009 they decided to make a rosé for the first time ‘as a white wine’, meaning not bled-off the red wine. The first vintage was 50% Merlot, 50% Cabernet Franc from selected parcels, which they use every year for rosé from soils with a high limestone content. The percentage of the varieties in the blend will vary from vintage to vintage. After gentle pressing with minimal skin contact, the juice of the two varieties is blended and ¾ of the blended juice is fermented in tank and one quarter is fermented in used 400l and 500l barrels followed by three months ageing.

The climate in 2017 was difficult, and their vineyards were partially hit by frost. As a result, the 2017 rosé, M de Mangot, has a higher percentage of Cabernet Franc with 70% and 30% Merlot. Tasted in March 2018, the fruit on this wine was still very closed, Very dry, with a long firm mineral structure, the oak was barely visible, other than giving extra weight and structure and a very subtle tannic finish. The acidity was long and mouth-watering. I loved the power and elegance of this rosé. I look forward to seeing how this wine will develop with some ageing. Yann told me that they are also aiming to produce a rosé which has low alcohol (under 12%), low sulphur and no additives.’

In every case of six bottles, each bottle has a different punt design

Château Brown

At Château Brown in Léognan, director Jean-Christophe Mau first started to think about making an oaked rosé in 2006, although not until 2012 did he launch his first vintage. His aim was to demonstrate the potential of Bordeaux rosé as a quality wine. The wine has consistently done well in tastings since Richard Bampfield’s first poshpinks tastings in London in 2013. The first vintage was a blend of 60% Cabernet Sauvignon and 40% Merlot, selected from plots with deep gravel soils, with an average vine age of twenty-two years. Manual harvesting, destemming and whole-bunch pressed, with four hours maceration and temperature-controlled fermentation in tank, made for a classic pale rosé, that was then finished with four months with battonage in one-year-old, lightly-toasted French oak barrels to produce a smooth, round mouthfeel, rather than imparting oak character. The 2017 vintage was 100% Merlot from the same plots as earlier vintages and made in the same way.

Château Brown rosé 2017 Pale pink with orange lights. Hints of vanillin oak on the nose combined with ripe, black, typical soft plummy Merlot fruit. On the palate, the oak is well integrated and not dominating, acting as the perfect foil for the opulent fruit with a creamy structure, concentrated weight and sweet oak flavours. The fruit is restrained rather than fruity, but black currants, cherries and plum fruit notes are all in evidence with a faint savoury tannic structure on the finish, and fresh citrus mineral acidity giving long length. (Tasted May 2018) I have to admit, I am not the biggest fan of Merlot rosés, as I find their soft opulence a little lacking in grip. Here however, the oak has given structure and weight, balancing the fruit.

Château Brown rosé 2017 Pale pink with orange lights. Hints of vanillin oak on the nose combined with ripe, black, typical soft plummy Merlot fruit. On the palate, the oak is well integrated and not dominating, acting as the perfect foil for the opulent fruit with a creamy structure, concentrated weight and sweet oak flavours. The fruit is restrained rather than fruity, but black currants, cherries and plum fruit notes are all in evidence with a faint savoury tannic structure on the finish, and fresh citrus mineral acidity giving long length. (Tasted May 2018) I have to admit, I am not the biggest fan of Merlot rosés, as I find their soft opulence a little lacking in grip. Here however, the oak has given structure and weight, balancing the fruit.

Conclusion

As with so many other regions, it is impossible to say there is one pink Bordeaux wine style. Clairet, fresh fruity rosé and more serious rosés such as these result in a range of styles. Vintage variation, region, varieties and winemaking… maybe we shall soon see additional indications on the appellation as in Provence? Bordeaux Rosé – St Emilion AOP or Bordeaux Rosé – St Julien AOP? Should saignée be indicated on the label? The weight and seriousness of these wines makes me think that they have good ageing potential, but sadly older vintages are not always available for what might be an interesting vertical tasting. I asked Anson whether she thought, with the number of top winemakers around in Bordeaux, whether we could start to expect a growth in more complex and serious rosés. ‘Possibly. The presence of clairet and the tradition of bleeding rosés off the red wines, has delayed the development of more serious rosés. However, there is great potential for more complex rosés, and top estates are taking this style seriously. Haut Bailly for example, is an estate to keep an eye on.’