Rediscovering Forgotten Grapes

At the recent Wine Mosaic conference, one of the facts that shocked participants most of all was the fact that the majority of wine is made with only a small percentage of the grape varieties available to us. 70% of French wine production comes from only 30% of the varieties grown, and this pattern is repeated globally.

6th century AD grape vine mosaic with Armenian inscription in chapel of St. Polyeuctos, Jerusalem

Less-used and lost varieties are important for several reasons. They enlarge the biodiversity of plants available, have been established for centuries and have adapted to different climates and regions and therefore have a unique taste of the terroir, and this combination of plant variation and different terroir enriches the range of wine tastes and styles available and reflects the different cultural tastes as well as maybe giving us a glimpse of tastes from the past.

6th century AD grape vine mosaic with Armenian inscription in chapel of St. Polyeuctos, Jerusalem

Less-used and lost varieties are important for several reasons. They enlarge the biodiversity of plants available, have been established for centuries and have adapted to different climates and regions and therefore have a unique taste of the terroir, and this combination of plant variation and different terroir enriches the range of wine tastes and styles available and reflects the different cultural tastes as well as maybe giving us a glimpse of tastes from the past.

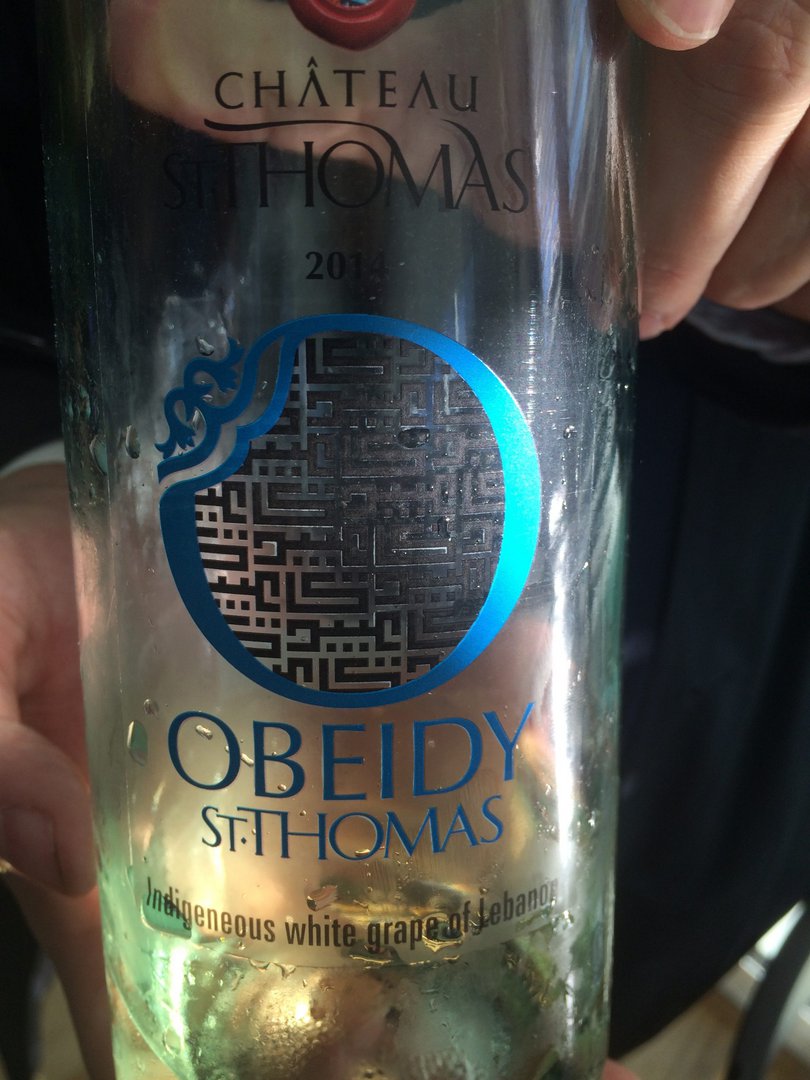

Chateau St Thomas, Obeidy

In many countries, the church preserved viticulture and wine-making after the fall of the Roman Empire and through the Middle Ages through their need for sacramental wine. In countries which were under Ottoman domination, where wine culture was not encouraged, their role was even more important. Vines were grown for table grapes and raisins, and, in a very limited way only, were permitted to remaining churches and Jewish communities in their production of sacramental wine and this has led, bizarrely, to these countries preserving more of their unique grape varieties. This year I have tasted an amazing range of indigenous varieties from countries either formerly part of the Ottoman Empire or touched by it: Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, Greece, Turkey, Lebanon and Israel. Wines made with indigenous grapes from the last two countries are still very small in quantity and include Chateau St Thomas in Lebanon’s ‘Obeidy’, whose DNA is currently being researched by José Vouillamoz.

Marawi vines trained in the Hebron Pergola style

In Israel, Dr. Shivi Drori, agriculture and oenology research coordinator at Ariel University for Samaria and the Jordan Rift has been researching local varieties over recent years. So far he has found over 120 unique varieties, including those found in the wild and from vineyards of table grapes discovered around the country. Winemakers at Recanati Winery who had taken part in his panel tastings, with other leading winemakers, of the micro-vinifications of these ‘indigenous’ varieties were particularly impressed with the high potential of the Marawi variety, and proposed making a larger quantity. Dr. Drori subsequently made contact with a Palestinian grower near Hebron who had a small plot, at 900m altitude, dry farmed and grown in the local ‘Hebron Pergola’ training system.

Recanati winemaker, Ido Lewinsohn, felt that Marawi produced a wine with similar characteristics to Chardonnay, so decided to barrel ferment in 2nd and 3rd fill Burgundian barrels and then age the wine for 9 months sur lie, but with no malolactic fermentation to preserve acidity.

Recanti's Marawi

On recently tasting this wine with winemaker Jo Ahearne MW, I noted that the wine had complex aromas of honey, nuts, lemon, peach and flowers. On the palate white flowers, pomelo, long mineral acidity with a broad, Chardonnay-like mouthfeel and hints of spicy dry pepperiness on the finish. Oak evident, but very well integrated and not overwhelming the fruit character of the wine. Only enough grapes were obtained to make around 2,500 bottles for the 2014 vintage, enough to distribute amongst the best restaurants in Tel Aviv, but no more. There are around 4000 bottles of the 2015 vintage currently in the cellar and Lewinsohn hopes to be able to start planting more Marawi in order to increase production.

The Marawi grapes for the 2014 wine came from the Judean Hills, south of Jerusalem, an area with a centuries-old viticultural tradition. Jerusalemite geographer al-Muqaddasi, wrote in 985AD of Hebron: ‘All the countryside around this town … has villages in every direction, with vineyards and grounds producing grapes and apples ...being fruit of unsurpassed excellence...Much of this fruit is dried, and sent to Egypt.’ Nothing much changed over the centuries. The Sacramento Daily Union reported in 1884 that ‘….. Fine raisins are made in Es-salt, east of Jordan, and also in Hebron. These are chiefly consumed in the country, for raisins are as much a staple article of food in every family as potatoes in America. The seedless raisins (which are very sweet) are sent to Egypt, and small quantities to other places…’ Both Christian and Jews were allowed to make some wine for their own use, resulting in monasteries with small vineyards and evidence of both communities paying taxes on their vineyards and wines.

Cremisan vineyard terraces

In the late nineteenth century al-Khader, near Hebron, was described by the Palestine Exploration Fund’s Survey of Western Palestine as a moderate-sized village with a ‘Greek church and convent.’ The Cremisan monastery was described as being surrounded by vineyards and olive groves; Italian monks began making wine there in 1885. In 1901, Frederic Haskin reported in the Los Angeles Herald from Bethlehem, just to the south of Jerusalem, that ‘…Christmas is a day of rest and enjoyment, celebrated by the consumption of the peculiar wine for which Bethlehem is famous among Syrians and infamous among Europeans and Americans.’ The vineyards in this region remained protected from phylloxera until the 1980s, when it decimated the local vineyards, reducing production by half. Research has been on-going, at the Hebron University, to find the right rootstocks for the vines for replanting. In 1997 the Cremesan Winery introduced modern equipment and in 2008 Riccardo Cotarella, a respected Italian winemaker, was brought in. He focused on the local grapes from al-Khader, Beit Jala, Beit Shemesh, and the Hebron area, and their 2011 ‘Star of Bethlehem’, (a blend of Jandali and Hamdani (Marawi)) impressed Jancis Robinson MW.

Remains of city wine press, Avdatin the Negev

Dr Drori has been looking into whether there is any relationship between the local and the classic European varieties, and between the indigenous varieties and ancient vines whose grape seeds have been found by archaeologists. University of Milan Professor Osvaldo Failla head of viticulture, as well as Professor Maria Stella Grando (FEM) are helping to analyse the DNA towards confirmation of the uniqueness of the local varieties collected in the survey. Simultaneously, a large project is about to collect and identify archaeological remains from a wide range of times. The grape seeds found in the excavations are analysed and compared to the varieties in the indigenous Israeli collection, to try to understand which cultivars were used for wine production in important historical periods. The Romans, Greeks, Byzantines, Crusaders and Ottomans may each have introduced different varieties. Tests are done by morphological 3D analysis, by laser cameras, and by DNA sequencing.

1,500 year old burnt grape seeds from Halutza in the Negev

In February 2015, excavations in the ancient city of Halutza (Elusa in Greek) in the Negev discovered grape seeds from the Babylonian era, 1500 years ago. DNA testing is being done to establish their type. Procopius wrote in the 6th century to a friend of the vineyards of Elusa ‘…weep at the sand being shifted by the wind stripping the vines naked to their roots’, perhaps referring to climate change, or the vineyards being abandoned. The wine of the Negev, along with vinum gazetum, was poplar at this time due to the rise in the number of monasteries and Christian pilgrims coming to visit. The wines were exported to all corners of the Mediterranean and were considered to be of very high quality and expensive.

A few of these varieties stand out as suitable for wine production. The three main red varieties are Balouti, Zeitani and Bituni. Balouti (which can be thin and harsh according to Adam Montefiori of Carmel Winery) and Zeitani are small-berried. In Hebrew, balut means ‘acorn’, and zayit means ‘olive’, so the names presumably were given for the size of the grapes.

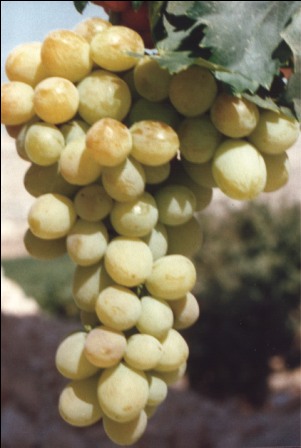

Marawi grapes

Three main white varieties are suitable for wine production, their large berries making them also suitable as table grapes (and thus ensuring their survival): Marawi (or Hamdani) is citrusy with long acidity, Jandali (or Djandali) is flowery and aromatic and Dabouki (the most widely planted).

Dabouki was considered a ‘work horse’ variety in the 1980s and 90s, and was largely used for distillation, believed by many to make the best base for the local spirit Arak. It was also used then to make cheap white wine when white wine consumption peaked – although always as part of a blend and never bottled as ‘Dabouki’. It was grown all over Israel, from Zichron Yaakov in the north to Ashkelon in the south. Plantings have declined as growers and winemakers have shifted to higher quality wines from international grapes, and it declined in popularity as a table grape due to its seeds. Seeds with a close DNA match have been found on archaeological sites.

Dabouki grapes Avi Feldstein has been using Dabouki both on its own and blended with Viognier. One of the attractions to him of using this variety is its expression of terroir. The grapes come from vines which are 40-60 years old, and Feldstein has been working on the trellising and sun-exposure of the grapes. A stony minerality on the palate with hints of nutty fruit and extra weight from some ageing sur lie, while the wine’s fruit aromas tend toward the floral and melon notes. 300 bottles were made in 2014, 800 in 2015 – a sign that not only of Feldstein's growing confidence with the potential of this variety, but also of a niche market for this wine. His next step will be to experiment with the traditional method of drying the grapes (which he is already doing with Argamon) before vinification to add to richness and intensity – but not yet making wine in amphorae. Personally, I am not so sure about the sensational headlines proclaiming these wines as recreations of the wines of King David and Jesus,although this certainly helped these grapes achieve publicity. We do not drink Bordeaux and exclaim that this is the wine drunk by Richard the Lionheart! Not only is the winemaking very different, but vines mutate and over 2000 years may have radically changed. The fact that top winemakers such as Lewinsohn and Feldstein are prepared to experiment and make quality wine from these varieties is a promising start in creating wines with a unique taste of the terroir, though they may remain just part of a select market compared with the sales of well-known international grapes. Plus, in a world in which global warming is threatening many vineyard regions, grapes which have learnt to adapt over the past 2000 years to heat and drought conditions are of great interest.