Moving on from Bull’s Blood

At the end of February I was invited to talk at the XIX Vine and Wine Conference at the Károly Esterházy University in Eger, on marketing Hungarian wine in a global context. Some of my research highlighted the fact that after Tokaj, Bull’s Blood was the most well known Hungarian wine in many countries. It also indicated that Bull’s Blood had a reputation for wine in the cheaper bulk wine category, with many wines generically labelled ‘Bull’s Blood’.

Ceiling of the conference hall at the Károly Esterházy University

The successful marketing campaign for Bull’s Blood refers to the legend of when the Ottoman Turks believed the Hungarians were drinking blood to fortify themselves before battle when they saw the red wine stains on their beards. Today, it is largely the entry level wines which are called Bull’s Blood: blended reds which are bottled in Eger. Mostly, serious Eger producers choose to call their wines by the Hungarian name bikavér, with maybe a passing nod to a bull on the label, such as those of Ferenc Tóth and János Bolyki.

The Bull on Ferenc Toth's label

After the conference I had a short time to visit cellars and taste wine, but, unlike previous visits when I had concentrated on the wine in the glass, this time I had in mind the question: how are Eger producers dealing with their Bull’s Blood image and how are they looking at raising their international reputation.

Geographical education was mentioned by a number of wine merchants and educators around the world as being important in the promotion of Hungarian wine. Many consumers, particularly outside of Europe, struggle to place Hungary on the map. Somewhere in Eastern Europe, in the former Communist bloc… While the latter is true, Hungary is historically and culturally closer to central Europe, the other half of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Eger town hall and wine drinking in the days of the Empire

Traces of the empire can still be seen in the impressive church and university in the major tourist centre of Eger, 90 minutes drive east of Budapest. The ruins of its old castle still stand on the hill overlooking the centre of town and the most northerly Ottoman minaret is still standing. The spas and walks in the surrounding mountains contribute to leisurely activities.

Bringing tourists and wine lovers to the vineyards, many with cellars and wine bars open to the public, are part of the growing wine tourism market in Hungary. Nimrod Kovacs has restored a run of old wine cellars in Eger itself, with deep vaulted cellars suitable for tastings and dinners; Tibor Gál has renovated 200 year-old stables in the centre of town into a modern, vibrant wine bar and St Andrea is in the process of expanding their premises to include a hotel and terrace to welcome visitors. I will be chairing a session on wine tourism in Hungary at the 10th Annual International Wine Tourism Conference, Exhibition & Workshop (IWINETC) in Budapest on 10th April.

The very modern and stylish wine bar at Tibor Gál's cellar

History was also regarded as an important part of selling Hungarian wine, especially in America and Asia where a sense of heritage is strongly appreciated. The blended bikavér wines are part of Hungarian wine tradition, blending varieties to make the best of every vintage in the same way that varieties are blended in Châteauneuf-du-Pape and Bordeaux. Under Communism, the blends had become a ‘soup’ of high-yielding grapes and work is now being done to create complex layers of fruit and structure.

The old Eger wine co-operative

Prior to phylloxera, Kadarka was the most popular red variety in Hungary, and was the major part of the blend. When Egri bikavér was created in 1936, vineyards were re-planted and growers had a choice of going in two directions: Kadarka with Ménoir (Médoc Noir) and Oporto (Kékoportó) to make rich wines, often with high alcohol, or lighter wines with a blend of Kadarka, Kékfrankos and Cabernets. Kadarka, with its reputation for uneven ripening and tendency to rot, was less reliable, while Kékfrankos, with its ability to do consistently well in both hot and cool vintages.

By the time Tibor Gál senior started planting vineyards in the 1990s, Hungarian indigenous varieties had the reputation of being little more than uninteresting bulk producers, and the way forward was by planting international varieties. Bordeaux blends were often seen (and still are by many around the country) as the epitome of high quality.

The issue of relative quality is particularly important when introducing a new wine region to the market. If only branded Bull’s Blood is seen as the point of reference for the quality of Egri bikavér, it can be difficult to introduce the higher quality wines. Back to education with visits to the region and tastings and masterclasses for prospective consumers is essential. This is particularly relevant in regions such as Eger where the wines are evolving.

It has only been in the last ten years that many producers have started to appreciate local varieties and to increase their plantings of Kékfrankos and Kadarka, amongst others. Not only that, but many are also taking cuttings from vineyards where the vines are showing great quality. As clones and cuttings are being valued, site selection is now becoming increasingly important. The University of Pécs, in the south, has been trialling a number of Kadarka clones with Zoltan Heimann in Szekszárd (who was also presenting at the conference), and some of these have been planted in Eger too.

The traditions of the best sites were lost under Communism, and it is only now – through research and trial and error – that these vineyards are being reclaimed. Producers are beginning to identify which sites are best for which variety and which clone, and to create greater complexity by planting a single variety in numerous locations. Eger has a big variety of terroirs, but because so many plots were planted with single varieties it is difficult to see the variations and how the soil affects the variety. Every plot was treated differently, and vine-growers are ‘re-learning’ how to blend different plots with one variety for complexity.

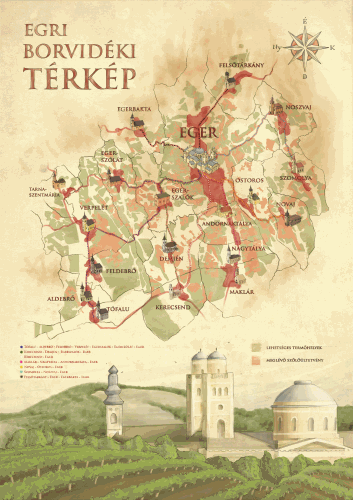

Map of the region around Eger

Sometimes a single site, such as Nagy-Eged, with its amazingly intense wines, is bottled as a single vineyard bikavér. Producers, in both Eger and Szekszárd (the other bikavér producing region), are considering whether single vineyard bikavér should be the top of the quality ladder? Or, should top sites they be blended into a premium cuvée? Should Eger’s volcanic sites be so identified in the light of the current fashion for volcanic wines?

Kékfrankos is being planted increasingly, with a higher percentage now permitted in the Egri bikavér blend – a minimum of 35% and a maximum of 65%. This is understandable, not only because the variety is reliable, but it is more easily marketable next to Austrian Blaufränkisch. This comparison to Austrian Blaufränkisch is not always helpful. Apart from different clones, the two styles are very different with the Austrian wines often having riper and more overt fruit compared to the more restrained Hungarian style.

Explaining the quality levels is essential. With the higher quality wines, there are lower yields and longer ageing to create greater fruit intensity is clear. But personally, I would like clearer labelling to indicate whether the wine is Classic or Grand Superior bikavér.

Length of ageing and yield contribute to wines with greater richness and intensity for the top end wines. Blends are based on Kékfrankos with various permutations of Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir, Syrah and Kadarka. Vintage variation plays a significant role in the styles of wine. Not just hot and dry or cold and wet years, but also subtle variation in the blends used.

Classic bikavér such as St Andrea’s Merengo has the typical red and blue fruit character of Kékfrankos-based Egri bikavér, with sour cherry and wild raspberry fruit up front and blue fruit and flower filling out the palate, fresh mineral acidity and crunchy tannins. Ferenc Toth’s Egri bikavér is smooth and silky, easy-drinking, mineral core, cool climate red and black berry fruit. Tibor Gál junior’s Titi bikavér has wild cherry fruit, spice and long chewy acidity with a mineral tannic core. In recent years he has started to reduce the amount of ageing to not overwhelm the fresh, cool climate fruit and acidity.

I named this distinctive red and blue fruit of Kékfrankos my ‘Donkey’ character, in reference to the film ‘Shrek’!

In a slightly different style, Nimrod Kovacs’s Rhapsody bikavér has a lower percentage of Kékfrankos and higher amounts of Pinot Noir, Syrah, Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon, giving black spicy fruit, with a noticeable touch of Syrah spice, supple tannins, balanced by a salty mineral structure.

The lower yields of Grand Superior are reflected in its higher intensity and richness. St Andrea’s Igazàn 2014 is powerful with wild berry fruit, very firm mouth-watering mineral acidity and dry, mouth-coating but silky tannins. Ferenc Tóth’s has grippy tannic structure with ripe cherry fruit, while Vilmos Thummerer’s includes a higher amount of Bordeaux varieties, giving more intense black fruit with powerful structural tannins.

Not everyone owns a prime site for a single vineyard bikavér, so there are fewer wines in this style. Nagy-Eged is the most important site, with both volcanic and limestone soils. St Andrea’s Nagy-Eged is amazingly perfumed with black fruits, spices, cloves and ripe chewy tannins. Thummerer’s Nagy-Eged has intense black colour, perfumed aromas, juicy blue-black fruit, firm structured inky tannins with smooth, silky acidity. Gál’s Single Vineyard Sik-hegy bikavér comes from the neighbouring site, and reveals the terroirs elegance with rich ripe fruit with blue floral notes, mineral core and fine structural tannins. Kovacs has chosen to use his Nagy-Eged vineyard to make a Kékfrankos varietal wine. His Grand Bleu Kékfrankos, grown at 500m, has intense black fruit, with supple velvety tannins and fresh salty acidity.

Lőrincz György with St Andrea's single vineyard Nagy-Eged

Cleverly building on both the Eger style of blends of many different varieties and the regions’ history, Eger winemakers launched, in 2011, a white bikavér called Egri Csillag – ‘stars of Eger’ – in reference to the eponymous book about the 16th century battle between the Hungarians and Ottomans, published in 1899. Tibor Gál came up with the idea after a particularly cool, wet vintage, and as a means of using up the myriad of small quantities of white varieties grown in the region. The appellation stipulates a minimum of 50% Hungarian varieties, with a minimum of four varieties. Gál’s Csillag has nine varieties. Which varieties used is less important than the style. A maximum 30% can be aromatic varieties.

It can be made in tank or barrel – a decision made to give winemakers choice of style but the market is confused at what an Egri Csillag is – range of varieties and ranging in style from crisp and fresh to heavily oaked. Should there be a Classic and a Superior level? under discussion. The wine can be released on 15th March, the date of the 1848 Revolution and the start of spring. Now, some twenty wineries make Csillag, with a combined volume of 1 million bottles. Gál’s Csillag 2017 has fresh green notes with creamy acidity, mineral length and peachy fruit and floral aromas opening out in the glass. Tóth’s Csillag 2017 has quite rich intense fruit, Thummerer also makes a Grand Superior Csillag from lower-yielding vines, with lees stirring and barrel ageing for a year.

Ferenc Csutorás For Eger producers, the past is providing inspiration. Producers such as Ferenc Csutorás and Péter Mészáros at Almagyar have spent the past 15 years researching in great detail the history of Egri Bikavér. A passion for quality clones, natural winemaking and old varieties has resulted in bikavérs made with high percentages of Kadarka, with vibrant acidity and ripe, spiced strawberry fruit (from cuttings selected from Balla Géza’s vineyards in Miniș in western Romania), and Ménoir, a bigger, blacker version of Kadarka. His salty mineral Olaszrizling, made with cuttings from Oszkár Maurer’s vineyards in northern Slovenia, are vibrant and exciting. Today, there is an energy and curiosity amongst winemakers, especially the young generation, exploring the potential in the region, exploring single varieties and looking at new terroirs and how they will develop. Bikavér has moved on from being Bull’s Blood and now needs the rest of the world to know.