Kadarka, Cadarca, Gamza

Based on a post first written and posted for Blue Danube Wines and a masterclass at RoVinHud in Romania, November 2016. Updated 16 March 2017 following a Kadarka tasting in Szekszárd.

Hungary is increasingly looking to its vinous history and indigenous varieties. There is a growing number of winemakers, who, with the help of research institutes like the one at Pécs, are replanting varieties which were almost lost during the phylloxera epidemic. Kadarka is one of those varieties now seeing a revival. It also happens to be my current favourite variety.

Kadarka

Recent research suggests that an ancestor of Kadarka, the Papazkarası variety found in the Strandja region of Thrace, on the border between Bulgaria and Turkey, was taken westwards and planted around Lake Scutari on the modern Albania-Montenegro border. There, it was crossed with a local variety, Skardarsko, creating Kadarka. It would have stayed little more than a local variety if political events had not intervened. In 1689 the Ottoman army defeated the Austrians and, in fear of further attacks, the locals moved north to the Pannonia Plain, taking with them their Kadarka vines. Today, Kadarka can also be found in southern Slovakia, in Recas and Minis in western Romania (where it is known as Cadarca), northern Serbia and in Bulgaria, where it is called Gamza.

Kadarka proved successful. By the 19th century it made up 60% of Hungarian vineyards. The Bikavér blends of Eger and Szekszárd included upto 60-70% of Kadarka, providing a touch of spice.

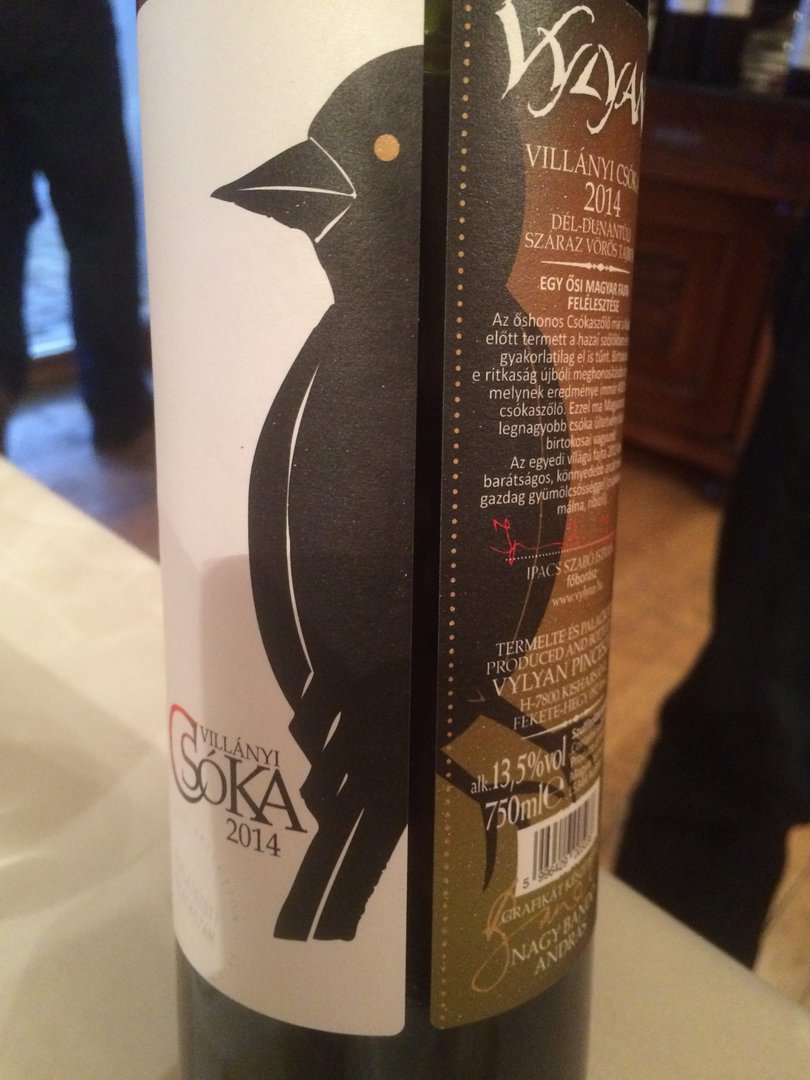

To counter Kadarka’s pale colour it was often blended with Csókaszőlő, the Jackdaw grape (today a very rare variety). Domaine Vylyan in Villány, southern Hungary, make a small amount of wine using the Csókaszőlő variety. Mészáros Pál in Szekszárd use a Mészáros clone from their vineyard which the research institute in Pécs discovered to be a field cross of Kadarka and Csókaszőlő which creates a darker, black cherry fruit wine.

Vylan's Csóka wine made with the Csókszolo variety

Kadarka’s delicacy led to winemakers using long maceration (which I think can unbalance the elegance in the few wines I have tasted made this way). In Szekszárd, Duszi’s Öreg tőkés and Eszterbauer’s Nagyapám (‘my grandfather’) are made in open top wooden vats with pigeage (punching down the skins), producing a Kadarka with the same silky tannins but greater structure.

Zoltán Polgár

Added richness was also gained by taking advantage of the thin skins and susceptibility to rot. Not all winemakers like the flavours of botrytis with Kadarka, but, in the right vintage, a small amount of botrytis (upto 15%) can add glycerol and body, and I did try a few good examples. St Andrea in Eger, Balla Géza in Romania and Vesztergombi in Szekszárd all make successful examples of dry red wine with a small percentage of botrytis to give richness.

In some years, sufficient botrytis can be achieved for a sweet red Kadarka. Balla Géza with Cadarissima and Zoltán Polgár in Villány have made good examples with luscious, ripe cherry and strawberry fruit.

Maybe it was this rich style which made Kadarka so highly regarded in the 19th century, that Hungarian composer, Franz Liszt annually sent some wine to Pope Pius IX.

Politics continued to play a part in Kadarka’s history. Under Communism, agricultural policies encouraged high-volume varieties. It did not favour the late-ripening, frost- and botrytis-sensitive Kadarka. In the late 1960s a high yielding clone, the so called ‘Füszeres (spicy) Kadarka’ or P9, was developed, but its large berries made it vulnerable to dropping its fruit under windy and rainy conditions and its fragile character meant it was not strong enough for mechanical harvesting. By the early 1970s, the authorities demanded wineries replace Kadarka with high yielding vines, almost bringing the variety to extinction. By 1989, Kadarka had dropped to 1% of Hungarian plantings.

Vida's 90 year old Kadarka vines

Some vineyards are lucky enough to have vines from before the introduction of P9, such as Vida’s Öreg tőkés and Sebestyén’s Kadarka. Both have an added savoury gamey complexity and rich wild berry fruit. Oszkár Maurer in Serbia even has a small plot of pre-phylloxera vines which he bottles under the name 1880, creating a delicate, floral version.

Planting is slowly increasing, now reaching 2% of the total, largely in Szekszárd, but also in Eger, Hajós-Baja and Kunság on the Great Plain. Estates such as Sauska in Villány and Heimann in Szekszárd are working with the Research Institute in Pécs, and have planted a variety of new clones. Heimann’s Céh Kereszt Kadarka 2015 was made from a blend of four new clones, P111, P115, P131, P147 and aged partly in first-filled Hungarian oak barrels. The 2015 vintage was difficult, but while Heimann’s P9 plot of Kadarka was delicate, with sour cherry and raspberry fruit, the new clones produced a wine which full of ripe black morello cherries, perfumed floral notes and the trademark silky tannins and fresh mouth-watering acidity.

On the limestone soils of Villány, Ildikó Markó, one of Sauska’s winemakers, says they started working with 15 clones, which they have reduced to the six best. Her favourites are the P124 and P127 clones. Vintage variations meant that the wines could vary between light and delicate to fuller-bodied more structural wines.

The jury is still out on which clones are the more successful. Desite the growing problems with P9, its floral delicacy is much admired, especially in Szekszárd while the newer clones can be produce much bigger, more structural wines in hotter vintages. Tasting the young 2016 vintage, I noticed I favoured the more delicate wines, in particular wines from Szent Gaál, Vida, Heimann, Sebestyen, Eszterbauers’ ‘Sogar’, Tüske, Takler and Neiner.

Young Kadarka vines, Szeleshát vineyards in Southern Szekszárd The P9 clones’ large bunches suffer from uneven ripening, which, compounded with Kadarka’s propensity to pale skins, means that some bunches have pale, almost unripe grapes, which some have used to make a white Kadarka. In March 2017 I tasted two white Kadarka from Hetenyi and Fritz wineries. Both wines had powerful citrus acidity with a vibrant green apple fruit which reminded me of Vinho Verde. Hetenyi's citrus fruit was almost candied lemon peel on the nose, while Fritz's was more weighty with apple and quince fruit on the palate. Alternatively, they were blended with riper grapes to make a pale red/ dark rosé Fuxli, the Szekszardi name for the schiller style wine. Today these grapes are used in lighter rosés or are pruned away to concentrate the vines energy on the ripening bunches. Dúzsi makes a light Kadarka rosé from ripe fruit, which has delicate red fruit, ripe creamy peach structure and fresh acidity. In Szekszárd, Kadarka is either bottled on its own or in the Szekszárdi Bikavér blend. On its own it shows Pinot Noir-style silky tannins, sour cherry and raspberry fruit, sometimes with fragrant floral rose notes and hints of spice, and high acidity. In hotter vintages, old vines and low yields, the wine can be bigger, richer with more black fruit and bigger tannins – but always retaining its suppleness and freshness. In the Bikavér blend, winemakers assure me that a small percentage is all that is needed to add spice and freshness to the blend. Too much Kadarka, and its fresh lighter style seems to allow the tannins of the other varieties in the blend to come to the fore. The more structured Kadarka wines can age well. Quality Kadarka will never be produced in vast quantities (although new clones are helping), which makes these wines even more of a delightful discovery. While producers who love Kadarka may curse its delicacy, its struggle to ripen, its susceptibility to rot, they have also learnt to turn these characteristics to their advantage to make a varied range of wines from light rosé, dark schiller, light red, rich red and even sweet wines.