Chardonnay - Limoux to Chablis regional styles

When we set out to get a feeling for the different styles of Chardonnay across France in 2021, we were expecting an easy conclusion, a starkly black and white contrast for all of our criteria.

Some producers had told us with great pride that their wines are rich and creamy, whilst others, with no less pride, proclaimed theirs to be light and crisp. We were dealing with hot dry climates and cool wet ones, and so many stark opposites that we were certain regional styles would jump out of the glass at us. Instead of answering "what" those styles are, here we are asking "if" there are distinguishable regional styles at all.

"We always look for freshness and finesse [but] the last few vintages have given us fuller, fatter wines, and the consumer seems to like that too" - Caryl Panman, Rives-Blanques

The first hurdle was consistent winemaking. Despite some producers aiming for rich butteriness (predominantly in and around Languedoc) and others for freshness (mostly Burgundy), the winemaking was for the most part very similar - 20-40% in oak, either barriques or demi-muids, for 6-9 months. Significant lees contact and batonnage, 100% Chardonnay, medium yields.

Throughout our tasting, we were very keen not to assess quality - our intention was categorically not to determine whether Chardonnay is better, or better value-for-money in one region or another. The majority of the wines were in the €14-24 range, with the least expensive retailing at €6 and the most expensive at €60. In practice, it was difficult of course to ignore some really outstanding quality, and it turned out that we did have a little bit of a soft spot for Limoux - although this should come as no surprise, as they’ve been cultivating a reputation for outstanding Chardonnays for a while now.

“Much easier to sell Burgundy at a given price. For the quality, it’s much cheaper in Languedoc” - Laurent Delaunay

We tasted with our regular tasting team (see our Bordeaux report), comprised of Elizabeth Gabay MW, Ben Bernheim, top sommeliers Julia and Bruno Scavo, and Antoine-Alex Mordiconi, a Nice-based wholesaler (XPA Les Vins d’Auteurs) with a love of Chardonnay. We were joined by guest-taster Burcak Desombre, a wine merchant from Istanbul. Check out the Cambridge Wine Blogger's International Chardonnay-Off for a similar tasting with a more global scope.

A small handful stood out particularly well with a particular favourite with all the tasters being Laurent Miquel’s La Croix single vineyard, a Pays d’Oc IGP. We had told the panel of tasters that the line-up included a 1er Cru Burgundy, and the consensus during the blind tasting was that this was it, matching our expectations both in quality and style, especially its masterful integration of the oak. More on this later.

“Consumers need a little taste of oak to recognise the variety as Chardonnay", Christophe Thibert, Domaine Thibert

Curiously, there was very little excessive oakiness or butteriness in any of the wines, and for most of the wines very little discernible oak at all, even if all of them spent at least a short time in oak. Whilst the absence of excessive oak could be down to chance, it clould also be attributable to a judicious choice of the samples, relying exclusively on producers in whom we already had confidence, especially in a post-ABC world. Had we included more mainstream, consumer-driven “American-targeted” brands, we might have had a more ‘caricatural’ selection. At any rate, we were afraid that some non-Burgundy wines would shout oakiness in an attempt to prove themselves, but this wasn’t the case - and our first line of investigation - "do producers make the buttery wines consumers love/hate" - came to an abrupt end.

Whole books have been written about Chardonnay and its incarnation in various appellations, and we weren’t setting out to rewrite them - our focus was firmly on a really wide ranging geographical selection in one single blind tasting. Whilst we kept terroir in mind, we were overall more interested in winemaking choices and styles.

We also conducted two further sub-tastings, starting with a non-expert panel the following day. Our demographic sample was older American women, which we thought was the stereotypical “Chardonnaaay” drinker. This, it turns out, is actually completely wrong. At any rate, the crowd favourite was overwhelmingly Lafage’s 2019 VdF Colline aux Fossiles. Although relatively traditional in its winemaking (30% new oak, cool fermentation, minimal malolactic, regular batonnage), we found that its ripeness of fruit almost had muscat undertones and a perfumed, citrussy sweetness.

Lafage La Colline aux Fossiles 2019

I can see why our chosen demographic liked it (and its gorgeous label), but sadly this section of the tasting did not really help us towards a conclusion about regional styles and consumer preferences.

“Entry-level consumers, especially in America, are looking for a more caricatural vision of Chardonnay” - Laurent Delaunay

After the consumer tasting, we took the three top wines from Limoux, Languedoc, and Burgundy, and asked an extremely promising young winemaker to join us in guessing which was which. Not one of the four of us tasting the selection accurately matched the glasses to their region, and there was widespread shock at the revelation that the favourite was once again a Pays d’Oc. The ensuing discussion revealed that any and all assumptions we thought we knew about the three regions had been proven wrong. Expectations were globally that Limoux would have the fiercest acidity, Languedoc the ripest but clunkiest fruit, and that Burgundy would be the most integrated and balanced were voiced, but apparently didn’t hold true in the tasting.

“Languedoc is great for its variety of terroirs, Limoux is among the best for Chardonnay, the best argilo-calcaire soil, good, altitude, plenty of rain” - Laurent Delaunay

Before the tasting, Limoux was the region from which we had the highest expectations. Today’s conventional wisdom is that Limoux offers outstanding value-for-money by combining Languedoc prices with a relatively high-altitude, inland coolness and humidity. The two producers we decided to include were Rives-Blanques, whose wines we generally adore, and Abbots & Delaunay, whose other (Pays d’Oc) Chardonnay first came to our attention last December. Theirs was a particularly interesting inclusion, as Laurent Delaunay is also at the head of Edouard Delaunay in Burgundy (see below), and his perspective on the contrast between the two regions was invaluable. He was very clear on the need to produce wine in a different style in the two regions, but equally clear on the difficulty of selling Languedoc Chardonnays at Burgundy prices, regardless of quality.

We also separately got to taste a fabulous vertical of Gérard Bertrand’s Aigle Royal Limoux Chardonnay going back to 2010, which will be featured in Decanter by the end of the year.

Both Limoux wines were difficult to place in the tasting, with everything from “Languedoc”, “possibly Limoux”, “warm climate but where???” and “benchmark Burgundy” appearing in our tasting notes. The ripeness of fruit balanced by fine acidity stood out, but possibly it was the ‘shape’ of the acidity which was a little different, with a long knife edge penetrating freshness compared to a broader acidity elsewhere. One thing that they had in common in our notes was their “benchmarkiness”, showing incredible and unmatched varietal typicity. The two were also standard-bearers for two very different winemaking styles, with Delaunay’s Le Palajo opting for citrus-crispness, and Rives-Blanques’ Odysée erring on the side of traditional, restrained-but-structural oakiness.

Abbots & Delaunay Domaine de la Métairie d'Alon Le Palajo 2018

Chateau Rives-Blanques Oydessée 2016

Vintage and ageing wasn’t a key part of the tasting (see Saint Hilaire’s Le Baron), but once again these two were excellent ambassadors for wines destined either for relatively prompt drinking or long ageing, representing here the 2019 and the 2016 vintages respectively. Most vintages, malolactic fermentation is avoided for them, although we didn't find this particularly noticeable in the tasting, even if on paper it should distinguish them quite evidently from Burgundy.

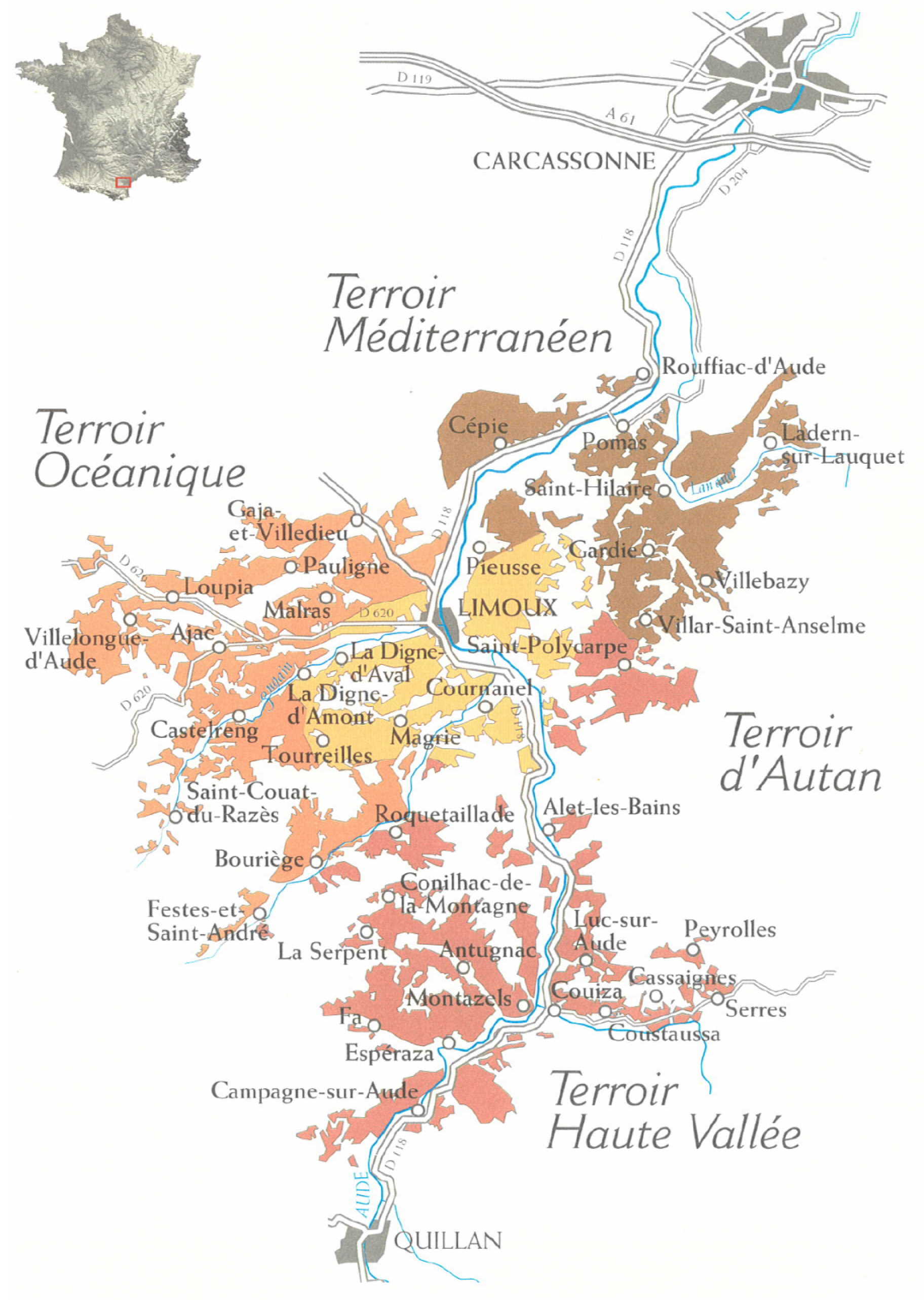

Without making this entire write-up entirely about Limoux (another time!) it's worth pointing out that Limoux AOP is not one monolithic block, but is made up of four terroirs. The 'Mediterranean', north-eastern-most chunk is 100-200m altitude, and relatively dry; the 'terroir d'Autan', centred on the town of Limoux, the most sheltered, is hotter and drier at 150-200m; the 'Oceanic' terroir, to the west, is the wettest and 200-300m altitude; and the 'vallée de l'Aude' is the highest, exceeding 300m altitude. Harvests are 2-4 weeks later in the two highest and wettest areas. The Domaine de la Métairie d'Alon (Abbots & Delaunay), in Magrie, is in the hot and dry 'terroir d'Autan', with the Palajo parcel at 280m, Gérard Bertrand's Domaine de l'Aigle in Roquetaillade, is higher up in the 'vallée de l'Aude'. Rives-Blanques, although in 'mediterranean' Cépie, sit on a 350m+ plateau. We felt that the wines really reflected their respective altitude and rainfall, with Le Palajo's crispness, the Aigle Royal's freshness and Odysée's ripe balance more evident than 'pure Limoux' character. Laurent Miquel's Lieu-Dit la Croix, similarly, sits at 350m, nestled in the Corbieres not too far away. The takeaway? Altitude matters.

Moving on from Limoux, Roussillon was a bit of an oddity - it’s not exactly the first area one looks at for Chardonnay. The style seemed to be little all over the place, in part due to some unusually innovative winemaking here, exemplified by Lafage’s Cadireta, vinified on Viognier lees for an intriguingly carnation and chamomile floral nose. Curiously, one taster identified almost all the Roussillon wines as being from Macon due to their ripe fruit and fresh acidity.

Laurent Miquel Solas 2019

Lafage Cadireta 2020

Arnaud de Villeneuve Chardonnay 2020

Elsewhere in Occitanie, we spiced things up in the tasting with two vintages of the same wine from Domaine Saint Hilaire, a 2016 and a 2018. These were the same two vintages as the other vertical in the line-up, Helena Hotéa's Pouilly Fuissé. By luck, in the random order assigned to the bottles, both 16s and both 18s were adjacent to each other, which made comparing them afterwards quite easy. Vintage variation and age dominated terroir in both cases. Both the 2018s were far more intensely tropical and exotically-fruity, whilst the 2016s were more evidently spicy and waxy.

Domaine St Hilaire La Baron 2016

Domaine St Hilaire Le Baron 2018

Helena Hotéa Pouilly Fuissé 2016

Helena Hotea Pouilly Fuissé 2018

"We would prefer not to release our oak-fermented Chardonnay until two years after the vintage, and have it available for sale for another four years" - Caryl Panman

As said earlier, one of the most interesting wines was Laurent Miquel's Lieu-Dit La Croix, a Pays d'Oc that wowed through its balance and beautiful integration of oak. We spoke to Laurent about what he thought contributed to its success, especially as he was very direct and stated that the wine was absolutely not representative of other Languedoc Chardonnays. The first warning bells went off for us when he explained that the agronome he worked with when planting the vineyard was from Chablis. Aware that yields would be low, and wanting to avoid heavy, over-intense fruit, he opted for high-yielding productive Chardonnay clones when his first choice of Albarino wasn't available in time.

"J'aime l'éclat la fraicheur. [...] Je pense qu'a Limoux on fait des excellents Chardonnays, mais je suis décu, ils sont parfois trop vineux, trop intenses" - Laurent Miquel

Similarly to other balanced Languedoc Chardonnays, he was clear that high-altitude (300m+), cool nights, lots of rainfall and windy days were key. The plots for La Croix often reach 85% humidity (in part thanks to a 50ha artificial lake), on days when other, lower-down parcels are at 45%.

"We planted Chardonnay by accident. We wanted Albarino..." - Laurent Miquel

Laurent Miquel Lieu dit la Croix 2018

Continuing northwards, Louis Latour is famous in Ardeche for Chardonnay, and as Antone-Alex commented during the tasting, every single bar and brasserie in the South-East seems to stock the Louis Latour Ardèche and Grand Ardèche wines. There was unfortunately an issue with our Ardeche sample, as it was highly reductive, but the Grand Ardeche was rather interesting. One of the most oak-evident of all the wines we tasted, it also divided opinion. The richness of the oak led some of us to think that it was warm-climate, possibly Languedoc, whilst others felt that its acidity and balance were positively cool-climate.

Louis Latour Grand Ardeche 2019

We were curious about how climate change was affecting Chardonnay, and whether some regions were feeling it more than others - is today's cool climate tomorrow's warm climate? Having hoped to present an answer here, we ended up with so much to say that it will have to wait until the next article. Suffice to say that everyone wanted less hail and frost!

Of all the major still Chardonnay-growing areas in France, Beaujolais was the only real absentee. It’s an area of huge commercial potential for the appellation, but unfortunately it’s not an area we know well enough to ensure that any sample we included in the tasting would be of the appropriate quality or typicity. If you feel that this is an area we should look into further and have some producers in mind who would be interested, do please let us know. We also didn't include Gascony or the Loire, despite their combined 1,500 hectares of Chardonnay, which will have to wait until another tasting and article.

As the Southern-most region of Burgundy proper, Macon was of particular interest - especially as its production is close to 90% Chardonnay. The wines we included in the tasting were from a really interesting producer with Romanian roots, Helena Hotea, and Domaine Thibert, whose owner gave us some excellent insight into where he felt the market was going. Unfortunately Thibert’s Macon-Verzé was corked, but behind this fault, we were able to detect elegant finesse with restrained fruit and long elegant acidity. Helena’s Saint-Veran was widely agreed to be “a Burgundy to have with cheese” through its sweet oaky weightiness.

Helena Hotea St Veran La Cote Rotie 2017

Helena Hotea Pouilly Fuissé Les Vignes au Dessus 2018

Helena Hotea Macon Vergisson 2018

Domaine Thibert Macon-Verzé 2017

Whilst not particularly evident in the tasting, there is one major line drawn just South of Macon, that we'll call the "Malolactic line". North of the line, malolactic fermentation was universal, and exceptionally rare South of it. On paper, Burgundy's use of malolactic and the South's avoidance of it may seem simple - but it was shocking how hard it was to detect during the tasting. Check out the Wine Enthusiast's article - When Did ‘Malo’ Become a Bad Word? for further reading.

"Très important de faire la malo, un chardonnay sans la malo c’est comme si on gomme le cépage" - Christophe Thibert

"As for malo, we prefer to avoid it, because we generally don’t think it adds anything positive to our wine, though there have been vintages where partial malolactic fermentation was not a bad thing" - Caryl Panman

"Pour la malo-lactique, nous ne la faisons jamais car nos vins manquent souvent d'acide malique, si nous la faisions, nos vins seraient trop lourds." - Edouard Rainaut, Domaine Saint-Hilaire

The classic Burgundy regions of the Côtes de Beaune and Côtes de Nuit were represented here at every level, from regional to village and one incredibly rare 1er Cru from Fixin. Innumerable books have been written about Burgundy’s Chardonnay, so we're avoiding focussing our attention here too greatly. We were particularly interested in Delaunay’s wines, having noticed a distinct Burgundian twist in his Pays d’Oc Chardonnay back in December. We spoke to Laurent Delaunay about his perspective of the evolution of Chardonnay over the past twenty years - he confirmed what others have said before: oaky, heavy styles are out.

We were therefore in two minds about what the tasting would reveal - would Burgundy indeed prove elegant and light, or would it on the contrary err on the side of tradition with heavier, more extracted fruit and greater intensity? We didn't come to an elegant conclusion here either. Delaunay's Charmont Hautes Cotes de Nuits was relatively oaky and structural, whilst his Saint Romain was far lighter, crisper, fresher and more citrussy - similarly to Domaine Joliet's Clos de la Perriere Fixin 1er Cru, which led several of us to assume Limoux for them both. Samuel Billaud's Grands Terroir Chablis was similarly light, crisp, and citrussy but with intensely ripe tropical notes, leading several tasters to describe it as "Burgundy but definitely not Chablis". Our overall takeaway from Burgundy was therefore quite simply that in our tasting, parcellar expression and winemaking seemed to dominate over regional style.

Edouard Delaunay Saint Romain 2018

Edouard Delaunay Charmont Hautes Cotes de Nuit 2019

Domaine Joliet Clos de la Perriere Fixin 1er Cru 2018

Samuel Billaud Chablis Les Grands Terroirs 2019

Bordeaux’s tiny Chardonnay production is a very well-kept secret. We’ve been really rather happy with the quality of white Bordeaux in recent years, so we had high hopes here. We’ve heard rumours of a few Chardonnays in the Gironde, and it’s such an unusual concept that they just had to be added to this tasting. The two included were Hubert de Bouard’s “Chardonnay”, and Domaine Puy Redon - an estate focussed wholly on Chardonay! Bruno Scavo, an excellent taster with outstanding knowledge of Bordeaux, spotted the Bordelais Chardonnay out of the 23 blind samples on his first pass, and after describing the ‘bordelais character’, it did make sense - the wines were slightly waxier, more tropical, grassy grapefruit and citrussy. (The brilliant acidity led us to first guess Limoux instead.) This was especially curious given their usage of Burgundian coopers, which suggests either extremely expressive Bordeaux terroir, or perhaps the usage of winemaking techniques usually reserved for Semillon and Sauvignon. At any rate, the Puy Redon especially was a really lovely wine, combining the best of both Bordeaux and Chardonnay in our opinion.

Puy Redon Chardonnay 2020

Hubert de Bouard 2020

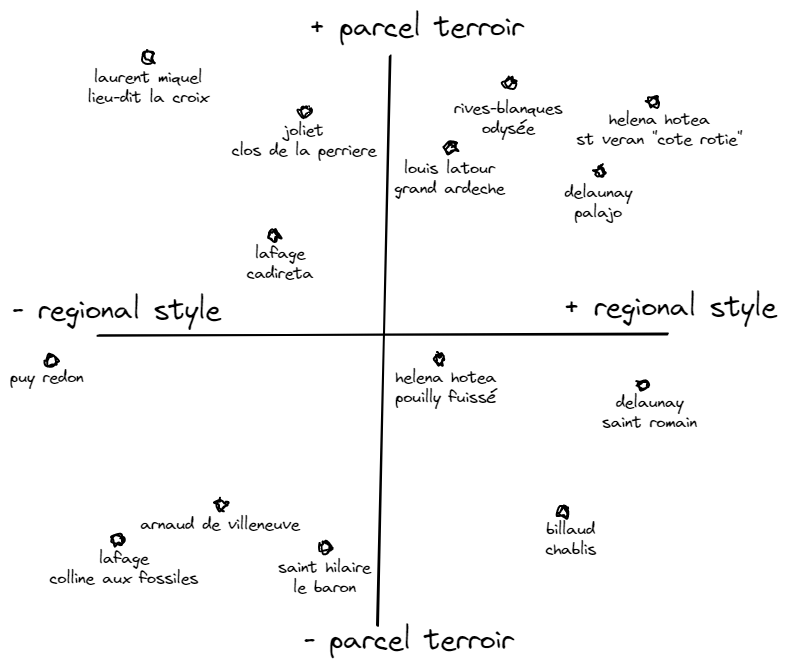

After this intriguingly expressive terroir, we went over our notes and the wines' tech sheets, and tried to attribute what we got from them to either regional style or specific parcellar terroir specificity, and finally made a breakthrough. About half the wines were single or limited parcels, and where we had struggled to identify regional styles, parcellar expression was significantly easier to detect in the wines. High altitude, wet micro-climates in Languedoc dominated any southern warmth, just as a quest for well-exposed slopes in Burgundy seemed to be dominating its natural cool climate.

"My wine is absolutely not representative of Chardonnay in Languedoc" - Laurent Miquel

Micro-climate and parcels shouted down climate and regional terroir, and we concluded that very few wines were representative of their region, instead flying the flag for their parcel or micro-climate. We put this together in the following graph:

We dreamt up this tasting with the goal of determining regional styles, and whether/where producers were actually making buttery Chardonnays. We threw half a dozen experienced tasters at the problem, and came to the conclusion that as Burgundy is losing its monopoly even in France in terms of volume and quality, it seems to have lost its monopoly of style too. In a fully blind tasting, regional styles are drowned out by vintage variation, similar winemaking, and most importantly, parcellar expression.

If you're interested in further reading on the topic, here's a small curated selection of articles that we found interesting and helpful in setting the scene for this article.

- BevAlc Insights’ 2021 Chardonnay Forecast

- Forbes - Most Wine Drinkers Don't Really Understand Chardonnay

- Guardian - Who says Chardonnay can't be cool

- SFChronicle - in defence of buttery Chardonnay

- Chardonnay: The Varietal for Every Consumer

- Wine Business International - Chardonnay trends

- "I just want a big, buttery Chardonnay"

- Kendall Jackson - How oak affects Chardonnay

Note on the tasting: of the 23 wines tasted, 2 were corked and 1 was irretrievably reductive - an abysmal rate that pushes us one step further towards glass caps and canned wine. Full tasting notes and information on the wines available on request.